2.2. Transition to agriculture

Humans had shaped the landscape long before the beginning of agriculture, for example, by lighting wildfires to allow wildlife to graze and thus facilitate hunting. However, the beginning of agriculture about 12,000 years ago was the starting point for a whole new scale of land use. Agriculture, which began in many places independently, meant the transformation of natural ecosystems into other forms of land use, such as farmland, livestock pastures, and permanently built-up areas.

In recent centuries, this development has accelerated, as can be seen from the Figure below. There are, of course, great uncertainties associated with historical land-use data. However, it is estimated that long before the start of Our Common Era, cropland accounted for less than one percent of the world's land area (about 130 million square kilometers excluding Antarctica). The proportion of land used for grazing was in the same range. By the turn of the 18th century, the share of cropland was in the order of a couple of percents, from which it has grown to the current share of about 12 percent. The area of grazing land, on the other hand, was in the order of 5% at the turn of the 18th century and is now about a quarter of the world's land area, although estimates of grazing land are more uncertain than cropland. Today, more than 50 million square kilometers of land is in agricultural use, which is about half of the habitable land, that is, land that does not include glaciers and barren land (such as deserts, dunes, and exposed rocks).

The figure shows the total area of cropland, grazing, and the built-up area in billions of hectares (billion ha). You can also view the figure by region by selecting ‘change country/region’. The area used for agriculture has increased from 440 million hectares at the beginning of the period to about 5 billion hectares today. The built-up area currently covers less than 0.5% of the earth's surface. The largest increase in the area used for agriculture began in the mid-18th century, and the growth of grazing land, in particular, has been rapid.

The transition to agriculture significantly affected the position of humans on earth. Modern human (Homo sapiens) has lived 95 percent of his/her/their entire two hundred thousand years of existence by collecting and hunting for his food. In prehistoric times, food consisted of tubers, stems and leaves, fruits, grains, nuts, fungi, insects, small invertebrates, mollusks, hunted herbivores, fish, and marine mammals. Although it is very uncertain how large the human population in prehistoric times was, it can nevertheless be said that it was very small compared to later times. For example, 500,000 years ago the earth was inhabited by an estimated 125,000 people, and at its lowest, the population was possibly only 10,000 people 75,000 years ago after the eruption of the Toba volcano. In the early days of agriculture, about 10,000 years ago, there were already an estimated 4 million people, but with agriculture, the population grew to 14 million in 5,000 years. 5000 years later, at the beginning of Our Common Era, there were probably as many as 250 million people.

Towards modern societies

It is typical to portray the history of humankind as a purposeful development. Indeed, the transition from the culture of hunter-gatherers to agriculture may seem like a great innovation and a step forward for humanity. It is, of course, self-evident that societies like today would not have developed without agriculture: it made it possible to build and develop life in one place, which led, for example, to the domestication of animals and the cultivation of crops, and to greater food production. Higher food production, on the other hand, also made it possible to redistribute labor in new ways, as the food produced by agriculture was sufficient not only for those working with livestock and agriculture but also for other members of the community.

However, several scholars, most famously Yuval Noah Harari, have pointed out that the transition to agriculture was a great disaster for people in prehistoric times. Food produced by farming communities was of lower nutritional value than food obtained through hunting and gathering, and when poorly nourished, the community was more susceptible to infectious diseases. This was exacerbated by a significantly higher population density. Although the diet was of poorer quality, the caloric intake was steady. As a result, significantly more children were born. Indeed, the population of agricultural communities grew rapidly compared to the previous period of hundreds of thousands of years.

In agricultural culture, work was also heavier and there was less free time, which meant that agricultural workers, who were physiologically adapted to the lives of hunter-gatherers, had many work-related illnesses and injuries. Still today, our bodies are mostly adapted to the hunter-gatherer way of life including their diet with lots of protein and fiber, and low in saturated fats and sugar.

Ten thousand years ago, people could not know that the transition to agriculture would, in time, allow the emergence of civilizations like the one we have today. Thus, the brave new world was hardly in the minds of the people as a motivation for the transition to agricultural culture. If life in agrarian culture was worse, then why in different parts of the world over a few thousand years, did people move on to become farmers? There is no certainty as to why people switched from hunting and gathering to agriculture, and there's no reason to assume that the same reason served as motivation everywhere on Earth. One logical explanation, however, is that because of excessive hunting, people lost their food supply and had to come up with new ways to produce food, by cultivating crops for example. Many other causes have also been suggested, including climate change.

In any case, agriculture made modern societies possible, and complex societies developed independently of each other across the world. At least eleven regions served as centers around which agriculture began to develop. It is difficult to determine exactly when agriculture began (in any part of the world), but two periods have been of particular interest to current research: the transition to the Holocene 12,000–9,000 years ago, and the middle phase of the Holocene 7,000–4,000 years ago. During the former period, agriculture began to develop, at least in East and Southwest Asia, and in the mid-Holocene, it developed for example in Africa, South Asia, and North America. The transition to agriculture did not occur in an instant, but in the early stages, agricultural and hunter-gatherer cultures coexisted.

Human influence on the plant and animal kingdom increased significantly around 11,500 years ago with the transition from the Pleistocene to the Holocene when humans began modifying the gene lineage of other organisms. Overall, two things contributed to the rise of agricultural culture: domestication of animals and plants, and cultivation.

Domestication refers to changing the genetic make-up of animals or plants as a result of human activity. In other words, humans began to breed animals and plants to better fit the demands of food production. This process was slow and meant in practice, among other things, favoring certain species and species traits. Thus, with domestication, wild animals became domestic animals and wild plants became crops.

Although domestication is often presented as a rapid process deliberately originated by humans, the process of domestication was in fact very complex, and the relationship between man, animals, and plants gradually changed over a long period of time. Agriculture also did not develop in the same way everywhere, but the main domesticated crops, for example, varied. For example on the American continent, animals were also domesticated thousands of years before crops. In Africa, the trend was the opposite.

Cultivation, on the other hand, means moving plants to places suitable for farming, such as farm fields. Also in the early days of agriculture, this meant clearing forests and other areas into fields and developing irrigation systems. Means for seed collection, processing and preservation were also developed within human communities.

The expansion of agricultural societies during the Holocene has also led to wider environmental impacts. The greatest environmental impact of agriculture was due to the fact that the population could now grow at an unprecedented rate, which has meant a denser population as well as higher consumption of natural resources. Environmental impacts were orders of magnitude larger than in smaller-scale Pleistocene communities. Forest clearance for fields, agricultural burning, erosion, exploitation of wood resources for fuel and construction, hunting, and fishing to feed larger populations resulted in cumulative and irreversible modifications of landscapes over increasingly large regions of the tropical, subtropical, and temperate world.

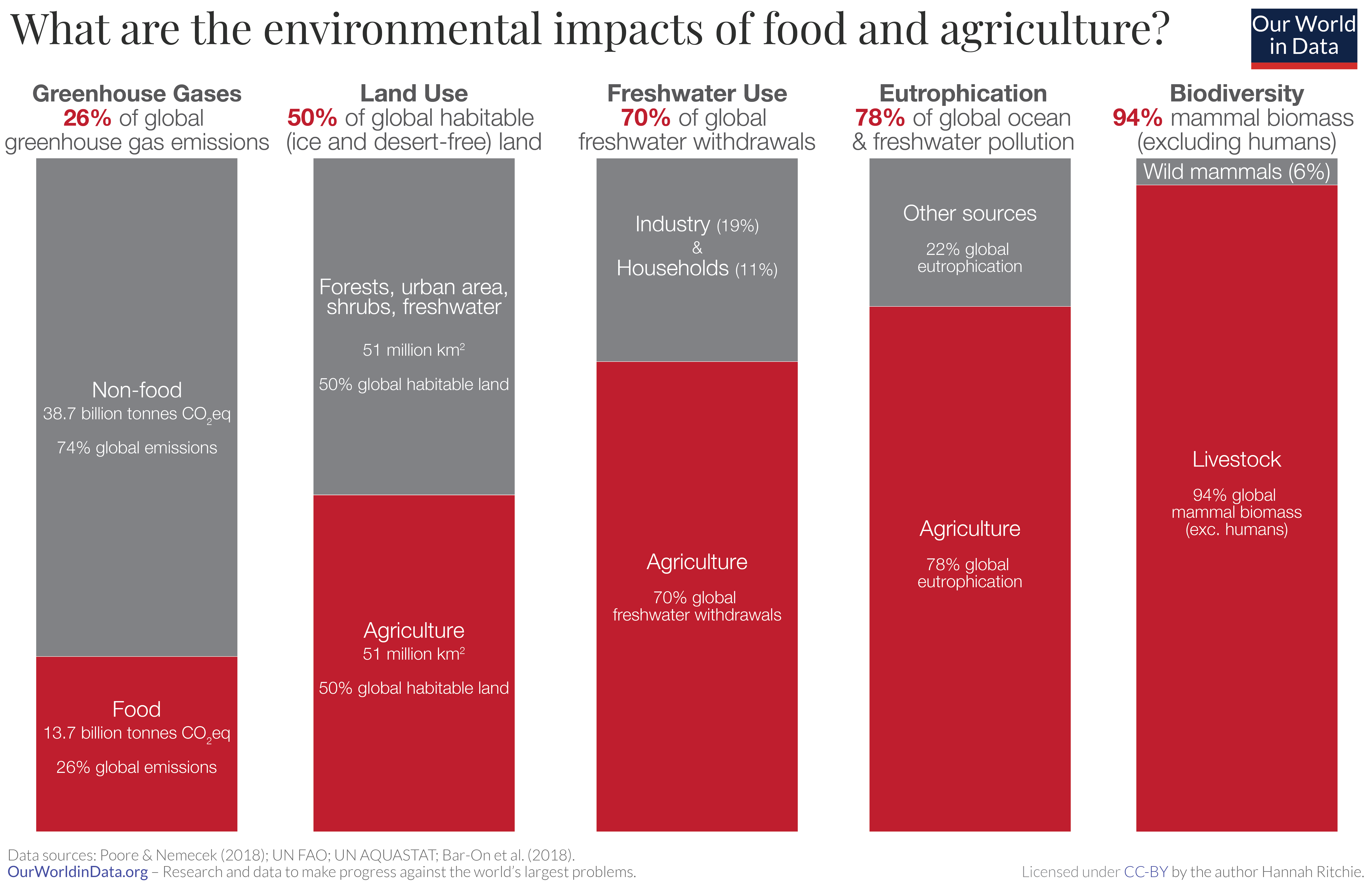

The figure shows the largest environmental impacts related to agriculture and the wider food chain. Today’s food chain is responsible e.g. for 26 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, 32 percent of acidification (not shown), and 78 percent of eutrophication.

Agriculture not only satisfies our most basic needs but also causes major global environmental problems, as can be seen from the figure above. Most of these emissions from the food chain (i.e. the journey of food "from field to table") come from farms: more than 60 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, 79 percent from acidification, and almost all (95%) from eutrophication. However, the environmental impact of agriculture varies greatly depending on what is produced. The same nutritional needs can be met with a hundred times less environmental impact by using plant-based foods instead of ruminant meat. In practice, this means that consumption habits and diets play a major role in reducing the environmental impact of agriculture.

Extra material online (in Finnish)

Miikka Tallavaara (2019): Mitä jos olisimme metsästäjä-keräilijöitä? Artikkeli helsinki.fi-sivustolla

Something to think about: we cannot stop farming, but we must reduce its environmental impact. What are the best ways to do this? You can share your reflections and discuss with other course participants on the page linked below.

Would you like to comment something on this section? Voluntary.